The Polaroid 210 “Automatic” Land Camera was the lower end model of the 200 line. According to the “Land List”, a fine resource for Polaroid information, the camera was produced between 1967 and 1969 and sold for a list price of $49.95. It was the first color-capable Polaroid to sell for under $50.00, and Polaroid made some 1,500,000 of them.

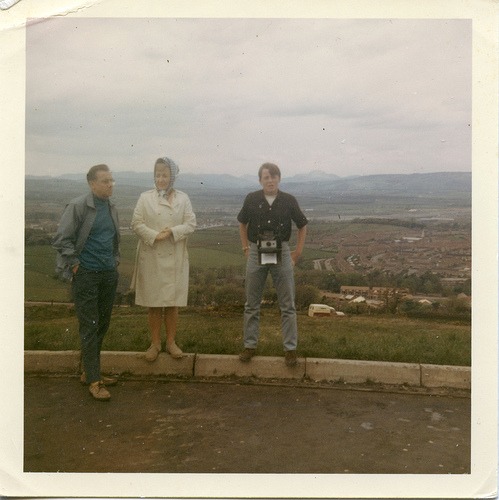

Also with my mum and dad. Someplace in Scotland.

I got one of those 210s back then. I still have it, too, although, much to my shame, I condemned the poor thing to life in the back of a closet on or about 1971 when I got my mitts on my first 35mm camera (a Mamiya-Sekor 1000 DTL that I had long coveted).

The term “35mm” had become a mantra to me over the year or two since I had acquired my 210. This, along with the svelte coolness of SLR aesthetics, meant the Mamiya now commanded all my attention, while the square and bulky 210, with its funky bellows and plastic body went the way of the dodo bird.

Assumptions of my 210’s extinction were premature it now seems, for I have recently undergone a metamorphosis. Polaroid Land Cameras are once again cool to me!

What’s more, I find that I am not alone. Film photography blogs and image hosting sites such as Flickr abound with Polaroid users and aficionados.

Why? The answer is hard to grasp given the distinctly lo-fi feature list of a rig like the 210.

With a plastic, two element lens, the 210 would never be the camera you’d turn to for crystal clear images. But if held with a steady hand and peered through with a sharp eye, it’s capable of decent results. I, sadly, must no longer be steady of hand or sharp of eye, for the images my 210 has recently produced have displayed a lack of clarity I would characterize as Diana-esque. (May I call them “dreamy” for the Lomo folks?)

The 210 has two film speed positions, 75 ASA for color film and 3000 for black and white. Film speed is selected with a switch on the top of the lens housing.

You have some manual control of the aperture. You can turn the bezel around the lens to various degrees of “Darken” or “Lighten.”

The shutter and light meter are powered by a 3v battery, and according to the website “Jim’s Polaroid Camera Collection” (http://polaroids.theskeltons.org/), another good source of Polaroid information, shutter speeds range from 1/1200 to 10 seconds. But the 210 lacks a tripod socket so you’d be challenged to get a decent long exposure.

Focusing the 210 is a hoot! You push a lever, linked mechanically to the lens housing, this way or that with the index fingers of each hand, thus positioning the lens nearer to, or further from, the film plane. Simultaneously a scale inside the viewfinder indicates the distance to your subject by means of an arrow that moves up or down through several distance ratings from 3 ½ ft to infinity.

Best of all, if your subject is a human being, Polaroid advised that distance can be estimated by placing the viewfinder’s infinity line at the top of your subject’s head then adjusting the movable indicator arrow to your subject’s chin. Actually, it works pretty well.

Taking a photo requires a sequence of steps that Polaroid helpfully guided you through by numbering key components on the camera.

- Focus by moving the lever with your index fingers

- Snap the picture using the red button

- Cock the shutter for the next exposure

- Pull the white paper tab to pop the leader out for film retrieval

Personally I prefer a 1-3-2-4 sequence, but that’s me.

With the 4 steps above completed, you’re ready to pull the film from the camera, thus initiating the development process.

You’ll have to wait before you peel the picture off the backing paper,…60 seconds, 90, …whatever, depending on the temperature.

For color film in temperatures below 65 degree F, Polaroid supplied a “cold clip.” This was made up of two aluminum plates hinged in book-like fashion with black tape. You placed your exposed film into the cold clip then kept in your pocket or under your arm for warmth while the film developed.

It was all very labor intensive actually, especially compared with modern photographic tools. But maybe this is some of the charm of Polaroid photography. It’s a tangible sense of involvement, of manipulating a mechanical device in search of an accurate representation of what you saw in your mind’s eye, however fleeting that image may have been.

Yet there’s a deeper appeal to the Polaroid process: it is laden with suspense! (Did I load that film right? Is the dark slide in the right place…? Will it come out when I pull it…? Where’s that white tab…? Oh yeah, there it is, whew! What if I pull the white tab and nothing happens…? Is 90 seconds too long a development time…? And so on!)

These questions and more melt away as you peel the film off and reveal the image. It may not look exactly like you thought it would, and the process is neither instant nor uncomplicated, but that picture was made by you and your Polaroid, and there is no other like it.

(You can pick up a Polaroid 210 and other varieties of Land Camera cheaply off E-bay. You’ll probably have to modify the battery connections for modern batteries, but this is easy.

Peel-apart film (FP-100c Color / FP-3000b BW) is manufactured by Fuji and readily available.

A note from Michael Raso

If you plan on purchasing your Polaroid “pack camera” from e-bay, remember to ask the seller if the battery compartment has any corrosion. If corrosion is present, you might want to consider holding out for a clean unit. I personally refurbish Polaroid Automatic Land Cameras and the 210 is available in our very own FPP Store.

About guest blogger Brian Moore

Brian writes mostly about soccer, in particular the European soccer leagues and especially the English Premier League. However, he has been an unapologetic camera nut since his early teens and although he never fully engaged with the digital camera world, he is delighted that he has recently been reawakened to the virtues of film photography.