Film Photography Podcast Episode 310 : The Photography of Tutankhamun’s Tomb!

Michael Raso, Matt Marrash, Owen McCafferty and Mark Dalzell are all ears as Leslie Lazenby highlights the exquisite glass plate photography of Harry Burton, official photographer for the 1922 Howard Carter expedition that lead to the discovery of King Tut’s tomb. And, Matt provides tips on resuscitating early 20th century photographic images printed on silver rich paper.

DOWNLOAD AUDIO PODCAST (Right Click / Save As)

The Man who Shot Tutankhamun

Blog by Leslie Lazenby

In 5th grade our elementary school class took a field trip to the Toledo Museum of Art. It was a very limited tour and teachers don’t have a lot of time to keep 5th graders interested and not giggling at the nude art sculptures. One gallery we were allowed to visit was the “Mummy room” as we called it. At the end of the day we got to visit the Museum’s gift shop. I bought one thing, a small, paper bound book about mummies. I still have it. Thus, in grade 5, began my love for the life and art of ancient Egypt. Of course with one’s love for this subject came a few quality coffee table books, some exclusive to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen. The images are nothing less than perfection.

above: Toledo Museum Of Art

Shame on me, I never went beyond the images to explore the photographer, and my love for photography is even older than my interest in the Egyptian Revival. YouTube suggested a video from TimeLine documentary series titled: The Photographs that Brought Tutankhamen to Life, The Man who Shot Tutankhamen. This introduced me to Harry Burton (1879-1940), the finest archeological photographer of his time.

The TimeLine documentary is not only about the discovery of the mummy’s tomb, but also about the photographer, his equipment and the adverse condition in which the images were made.

The documentary highlights him and his working relationship with Carter and Lord Carnarvon. For you gear heads, the equipment he used was a Sinclair Una 1/2 plate camera. (61/2”x41/2’ – 121 mm x165 mm). Also discussed is how he added light to the dark chambers (since working lights were not always the best for imaging) and even his temporary darkroom that was set up in another tomb. Although film was available in 1922, he used glass plates, feeling they were superior.

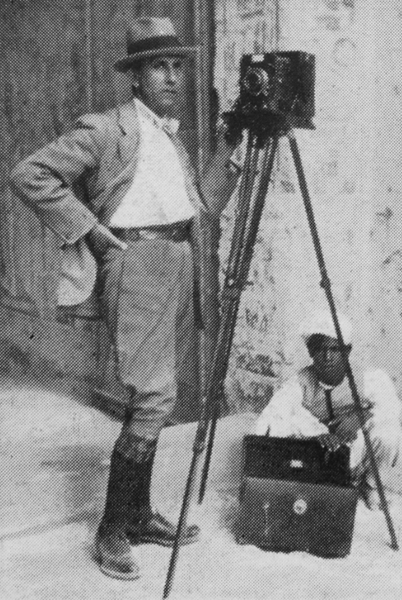

Photographer Harry Burton

At that time of course, the photos were black and white, yet many later were colorized and colored lantern slides were made available for public lecture. Today, the stills are an extremely valuable research tool due to their high resolution and detail. Until 2016 they still surpassed any flat imaging capture. He shot not only “all over” scenes but close up work as well, and also the people involved in the exploration.

When a modern photographer reproduced the process of shooting in those conditions, one thing he noted were Burton’s dust free glass plates. Modern photographers are unable to keep their negatives as clean.

.

As Burton had done, he set up the temporary darkroom close by in another tomb to load plates and process the negatives. Carter had a home a few miles from the site, but timing was important and that was not close enough for Burton. Carter would not move on with the exploration until the previous day’s images were processed and approved. Modern photographers and Burton located their temporary darkooms in the nearby tomb, KV55, only meters from the entrance of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Note that everything had to be supplied from a remote location, think about it, not only materials like boxes of plates and camera gear but chemistry and water.

I found this TimeLine episode not only entertaining but gained a great appreciation for Burton and his photographic technical perfection. A full shooting, proper equipment and processing reenactment were filmed. Even though it was Carter’s discovery, Burton made it available to the world. It began another era of Egyptomania and the Art Deco period. He continued to be the premier archeological photographer until his death in 1940.