UPDATED – January 26, 2024

Editor’s note: All of us here at the Film Photography Project are dedicated to the preservation (and continued manufacture) of all still and motion picture film formats. Unfortunately, some formats are still somewhat lost – with no new film production. One such format that desperately needs attention is 126 Cartridge Film. Although 35mm in width, it’s sprocketed differently and is housed in an awesome, convenient plastic cassette (that just drops right in your camera). With no new 126 film being produced, the Film Photography Project has taken upon itself to create options in 2024 (and beyond) so that we all can still enjoy shooting our beloved Kodak Instamatic 126 cameras (and our fancier 126 Reflex Cameras too). Below are the options (available in the FPP On-Line Store as of this writing)

The FAKMATIC 35mm to 126 Adapter

What is it? This ingenious re-usable adapter (imported from CameraHack, Italy) allows you to spool 35mm film into the adapter so you can shoot with your favorite 126 camera. Video HERE.

Re-Load 35mm Film into Vintage 126 Cassettes

It can be tricky – Michael Raso offers a demo with some tips in this VIDEO. About once a year, the FPP offers pre-loaded 126 cassettes. You can check HERE.

Shoot Expired 126 Film

There are still thousands of expired “old new stock” out there in thrift shops and on eBay.com. Look for Kodak Gold Color or Kodak Verichrome Pan BW. Avoid Kodachrome as it can no longer be processed.

126 Format History

by Owen McCafferty

If you were a child of the late 1960’s, chances are many of your childhood memories were captured by your family on a trusty Kodak Instamatic camera equipped with 126 film. The 126 format, introduced by Kodak in 1963, became one of the most iconic and recognizable formats of this era. Cameras loaded with the black cartridge and magicubes became a staple at holiday gatherings, proms, weddings, and everything in between. This convenient, nifty film format was very popular with the average photography consumer almost immediately after it came to market, but what happened to it? And most importantly, what’s its future?

Before we get into its current status and its future, let’s first take a quick trip back in history. The year is 1963, and Kodak is just about to announce a brand-new film format and a range of cameras to go with it. This new format, called Kodapak (known by most people under its assigned number, 126) was in part introduced to solve a problem that faced most camera users of the day: eliminating the bulky process of loading roll film into the camera. This new film was loaded into a plastic cartridge that was all self-contained; all the user needed to do was pop the cartridge into the back of the camera, wind it a few times, and they were ready to shoot! It was in a way, revolutionary.

The cartridges were loaded with film that was the same width of 35mm film, but there were a few features that made it very unique. First, and probably the most distinguishable, is the square format of the photos. The cameras produced images that, once masked, were 26.5 x 26.5mm. Therefore, when processed and printed, the film produced square images that most consumers were already used to from their 620 and 127 format cameras which dominated the consumer market at the time. The film also featured only one perforation per photo, located at the lower left of each image. Inside the camera was a pin that, once engaged with that perforation, would keep the operator from winding the camera any further. Another unique feature of 126 film was the use of backing paper which displayed the winding instructions and film counter for the user on the back of the camera.

above: The difference between 126 and 35mm film. / Below: The classic square print – the result from a Keystone 125x camera. Image Thanksgiving 1969 – courtesy of Michael Raso

Even though the new format was revolutionary in design at the time, these features made the user picture-taking-experience somewhat similar to what the average person was already used to. Most importantly, it eliminated the step of having to load roll film which most users hated doing. 127 and 620 roll films needed to be loaded, manually pulled through the camera, and threaded into the take-up spool. This meant that if you were shooting something important like Jimmy’s first steps, you had better hope that you don’t run out of film because loading and unloading your camera could take almost a minute to do—more if you weren’t able to sit down to do it. And you better hope you don’t drop that roll of film either—otherwise your reel goes rolling along the floor spoiling all your photos in a matter of seconds.

You might be asking ‘what about 35mm film?’ Why didn’t people just use that? Sure, it’s not in a self-contained cartridge that requires no threading, but it’s still pretty easy!’

And that’s a great point. But remember that it’s 1963, and most 35mm cameras on the market were expensive (even the consumer models) and mostly geared towards people who wanted to take slides. The cameras were also fairly difficult for the average Joe on the street to use, and the format just didn’t seem to have the reputation with consumers that other larger roll films like 127 and 620 did. Which brings us to the next important part of this story: The Instamatic cameras.

The success and popularity of 126 film couldn’t have been obtained without a camera that was designed with the same concept of ease-of-use in mind. Kodak introduced the Instamatic 100 to Americans in 1963 and it cost $16.00 (about $140 in 2018 money.) The camera had a fixed shutter speed, aperture, and focus and had a built-in flash which popped up from the body of the camera and held AG-1 bulbs for flash photos. The camera was simple, well built, inexpensive, and easy to use. The perfect pair with a film format that was created with the same concepts in mind.

above: The original Kodak Instamatic 100 camera

Over the years, Kodak (and MANY other manufacturers) went on to make many different Instamatic 126 cameras. Some dabbled into the pro-sumer market by offering the ability to change shutter speeds and aperture, as well as add an electronic flash.

In the late 1960’s, Sylvania introduce the Magicube, a new flash system that looked almost identical to the Flashcubes they invented a bit earlier but didn’t require the use of batteries. In 1970, Kodak introduced the X-series of Instamatics—the X-15 in particular became an iconic camera itself and is often the camera that pops into people’s head when they think of the format. This new flash system just added to the convenience of the format, furthering its popularity. Later on in 1975, the X-15 was modified to accept the Flip-Flash system.

above: The iconic 1976 Kodak X-15-F 126 camera.

Kodak didn’t stop at the 126 format—they used the concept of Instamatic as a new way of thinking about photography and a new brand. This included movie film, as the new Super 8 format was introduced in 1965 with its own line of easy-to-use Instamatic movie cameras.

In 1972 another iconic format was introduced to consumers: the Pocket Instamatic, assigned the more familiar format number 110. These cameras featured the same concept in film loading as the 126, but was significantly smaller, allowing the use of cameras that could easily fit into a user’s pocket.

By the mid to late 1980’s however, the film seemed disappear. In 1988, Kodak ceased production of its last 126 Instamatic camera, the X-15F, and by 1999, Kodak stopped making 126 film altogether. So, what happened?

There doesn’t appear to be one single thing that lead to the demise of 126 film, but rather a culmination of things in the photography market that ushered it out—some less obvious than others. When Kodak introduced the 110 format in 1973, it took off, and became even more popular by the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Consumers seemed to like the compactness of the cameras and the film, and because later models featured built-in electronic flashes, they were more convenient.

In addition to the popularity of the 110 format, other camera manufacturers like Canon, Nikon, and Minolta, were making leaps and bounds in technological advances of 35mm cameras. They were becoming smaller, lighter, easier to use, and cheaper. The 35mm format was touted as producing better quality photographs, and the cameras were better made.

Kodak produced another new format, Disc Film in 1982 which was almost a complete flop, as the tiny negatives produced almost comically terrible prints with horrible grainy-ness. All of the sudden, consumers seemed to be attracted to the large and sharp prints 35mm could produce and by the early to mid 1990’s, 35mm became the format of choice for many consumers.

126 therefore had a slow death. After 1999, when Kodak discontinued production of the format, most people turned to Ferrania film in Italy, who was still manufacturing the film under the Solaris brand. But, after Ferrania filed for bankruptcy around 2007, the 126 supply slowly dwindled and by around 2009/2010, it started to disappear completely.

Which leads us to today, 2018. Where is 126 film today and what’s its future?

There are no manufacturers making new 126 film on the market as of yet. But there are some solutions for those looking to utilize their fun (and cheap to buy!) Instamatics.

One of the newest solutions is the FakMatic adapter, which allows you to shoot 35mm film in your 126 camera via a 3D printed adapter made by CamerHack in Italy. You can purchase your very own at the FPP store here.

If you can’t get your hands on the FakMatic but have an old 126 cartridge, you can also load 35mm film into it and shoot that way. Here’s a video link that explains how.

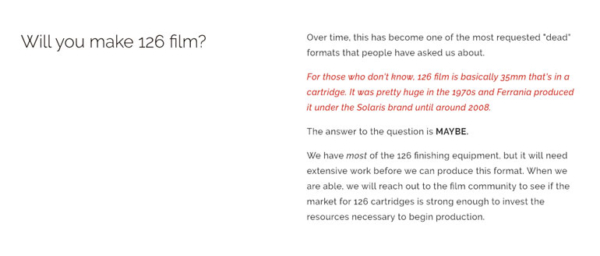

What’s the future of 126 film? That’s still unknown, but the format’s best bet for resurrection is likely from the very company that discontinued it: Ferannia film. Ferannia film was salvaged from complete destruction by a team of passionate film professionals and former employees via a Kickstarter a few years ago. Ferannia has said that they did salvage and save most of the old equipment needed to produce 126 film from being chucked out. Here’s what they’ve said on the subject:

It’s not exactly the BEST news, but there is a possibility—and we have to hope that the film community voices their support of Ferannia to reintroduce the format in the future. Considering the popularity of square format photos today (thanks, Instagram) and the fact that 126 Instamatics can be found at almost any thrift store in the country for practically pennies, 126 may just have a bright future ahead!

——————-

About the author

Owen McCafferty is a native Clevelander who has been shooting analog movie and still film since the age of 12 in 2002. When he’s not out shooting, he works in product development and innovation for a firm in Cleveland.